My writings - and those of others.

Insights and a Question

I’m quoting from Matthew Fox today as he examines the need for a sense of the sacred - and contends that the opposite of evil is not good - it’s the sense of the sacred. For a renewed discovery of the sacred, he turns to the astronauts - whose experience, he says turns them into cosmonauts.

“That beautiful, warm, living object looked so fragile, so delicate, that if you touched it with a finger it would crumble and fall apart.” James Irwin, Apollo mission.

"On the return trip home, gazing through 240,000 miles of space toward the stars and the planet from which I had come, I suddenly experienced the universe as intelligent, loving, harmonious. . . "My view of our planet was a glimpse of divinity." - Edgar Mitchell, the Moon landing

And here was a statement from Russian cosmonaut Boris Volynov:

“During a space flight, the psyche of each astronaut is reshaped. Having seen the sun, the stars, and our planet, you become more full of life, softer. You begin to look at all living things with great trepidation and you begin to be more kind and patient with the people around you. At any rate, that is what happened to me.”

Matthew Fox then asks: What would it mean if these testimonies from space truly coursed through decision-makers in various countries from which they come?

What indeed!

Deep Time and Deep Work

“Deep” is in and these two terms will yield results when you Google them or check them out in Wikipedia as I just did.

Google says this:

Deep time" refers to the time scale of geologic events, which is vastly, almost unimaginably greater than the time scale of human lives and human plans. It is one of geology's great gifts to the world's set of important ideas.

Here is what Wikipedia has to say:

“Deep time is a term introduced and applied by John McPhee to the concept of geologic time in his Basin and Range (1981), parts of which originally appeared in the New Yorker magazine.The philosophical concept of geological time was developed in the 18th century by Scottish geologist James Hutton (1726–1797); his "system of the habitable Earth" was a deistic mechanism keeping the world eternally suitable for humans. The modern concept shows huge changes over the age of the Earth which has been determined to be, after a long and complex history of developments, around 4.55 billion years.

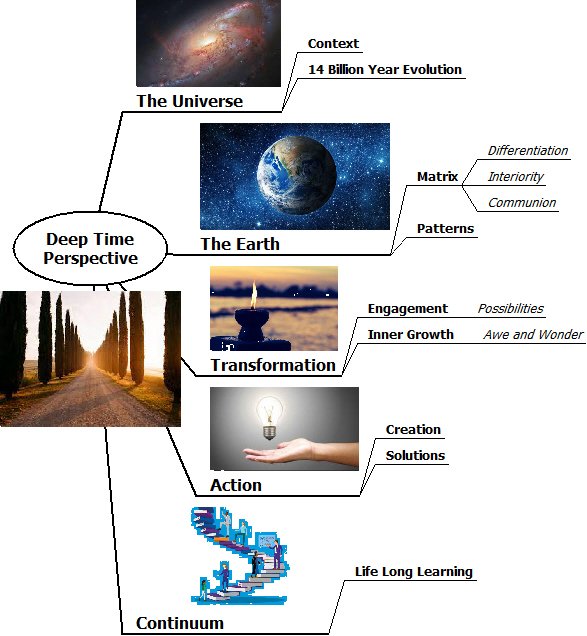

The DeepTime Network tries to come from a broad perspective, though it doesn’t have an emphasis on geology and might benefit from more references to it. I created a map of the main components of the perspective just to provide a big picture view.

When you Google Cal Newport, you go straight to the book order site loved and despised by all. Deep Work is the title of a book by Cal Newport. Wikipedia tells us this about him.

“Newport coined the term "deep work," in his book Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World (2016) which refers to studying for focused chunks of time without distractions such as email and social media. He challenges the belief that participation in social media is important for career capital. In 2017, he began advocating for "digital minimalism. In 2021, he began referring to the role email and chat play in what he calls "the hyperactive hive mind".

I’ve read the book and it has some useful advice for a curious and distractable person like me. I’m also currently participating in a DTN course that attempts to prepare leaders in to use the new cosmology.

Much of its framework depends on the writing and teaching of Thomas Berry, a Passionist priest and a cultural historian who pondered the impact of culture and religion on our attitude toward the environment. He called as early as 1978 for a New Story that incorporated the learnings of science and religion. The purpose was to create a new spiritual framework for all institutional forms that included the entire universe story into religious and cultural history – especially those of the West. Later he framed this as a journey, a sequence of non-reversible events. To follow through would have a profound impact on education, government, law and world religions themselves. The assigment went far beyond simply learning about other faiths through social gatherings, study groups or visits to places of worship, but getting down to the business of saving our common planet together.

Berry’s impact on his graduate students was immense and his teachings have found an impressive home at Yale in the Yale Forum for Religion and Ecology. There are solid resources there which come for free to all who are interested. One of the aspects I admire is their thoroughness. There is a continuing relationship with world religions. In contrast the DTN is going more in the direction of creating a new one – for the spiritual but not religious. Some of the participants are RC nuns, who have every reason to distrust their hierarchy. Much of the energy of some has a stamp of Berry’s teaching. He was willing to spend lots of time teaching them and they were good students. But other participants may be enthusiasts of their own individual spiritualities that used to be called New Age – and which Berry warned against.

I find it really interesting to spend time in worlds unlike those of my former not-for profit one or my institutional church one. At times I have to draw back a bit from endless new processes and their acronyms so much loved in America. Any workshop attender has been there. The temptation is to go down rabbit-holes of suggestions to explore that sometimes are a waste of time – though at least I would not say, dangerous. I’m starting to become impatient as to how many websites suggested by participants are focusing mainly on sales and donations even with a url of .org. My own .url is a leftover from the days I actually did have a business.

There is sometimes a tendency to think in such courses that a quotation substitutes for a entire body of learning. Understanding and absorbing any worthwhile body of work must be gained through serious study. Such a body of work is not like a short poem – a very good one does have the capability of creating a universe of its own. Some sessions on life long learning are coming up. I have some good track record in that area - long life a t least - of longer duration than the presenting academics. We’ll see how they relate to deep time and deep work.

Bring a rock

I’ve been taking a course called “Understanding the new Cosmology - and one of the recent lessons suggested in advance, “Bring a Rock”. It’s a little harder for someone in a large city to find one - until one starts looking and find them decorating borders of flowerbeds everywhere.

Rocks for some appear to be pets - less walking and feeding perhaps. Kids love painting them. They are actually good to have around a reminder of how old the universe really is. Cosmologist Brian Swimme reminded us that once upon a time they were probably aflame before settling down to becoming mountains that gradually wore down to the size we can pick up. They are a solid mass of minerals that can be categorized and also have chemical components. We’ve been using them for about two and a half million years for building and mining.

They make good indoor company by being just there - and how young we are in comparison. We know more about planet earth from the study of geology than many cultures that preceded us.

Thomas and Sallie

The following is an essay that I have written for members of the Deep Time Network and can also be accessed on that site. It is something of a departure from the usual posts here - but an important element in dealing with our climate crisis.

Thomas and Sallie

As a movie fan, I might have been tempted to title this essay When Thomas Met Sallie but I will not go there. Instead, I want to pay tribute to two teachers and prophets, Thomas Berry and Sallie McFague. Through their writings, they have influenced me greatly in the later years of my life, with their prophetic sense of where we find ourselves now – as well as their pointing to the way we must go. While their messages are often directed to North American audiences, they reach far beyond those shores.

What is their influence for me? In a nutshell. It involves the rethinking of my faith tradition and how, in spite of all its virtues, it has had a negative impact on how we view the earth. I am a cradle Anglican, a graduate of a college in the University of Toronto that required me to take religious studies in each of my four undergraduate years, a widow of an Anglican priest and an active member and volunteer of my parish church and for its regional and national bodies. It has resembled swimming in an ocean with little knowledge of other oceans. It’s not that I have never questioned my faith or was less than satisfied with the answers. It’s also that I have often failed to ask the right questions.

In the first try at this essay, I handled each author sequentially and delved into their writings in chronological order. Two helpful readers pointed out that this was really two essays and if I wished to make a comparison, the methodology was not helpful. I’ll now proceed to review how they converge and how they differ.

I did meet Sallie McFague briefly at Rivendell, a beautiful retreat center on Bowen Island near Vancouver. My sister-in-law, a staff volunteer there, had recommended one of her books and I told Sallie I was reading it. “Which one?”, she asked, somewhat sharply. Life Abundant, I replied. She relaxed, saying, “I’m so glad. I’ve been writing the same book for twenty years and this is the best version so far”. I await the final one in November 2021 that will be published posthumously two years after her death in 2019. Like Thomas Berry, she had a long and productive life.

Sallie McFague had a somewhat conventional academic career, but it was one filled with growth and reassessment. Born in 1933 in Quincy Massachusetts, her first degree was in English from Smith College in 1955, just as I was starting a similar degree at Trinity College, Toronto. She then pursued a Bachelor of Divinity at Yale, followed by a master’s degree and a doctorate there. She taught briefly at both Smith and Yale and moved to Vanderbilt Divinity School in 1970, where she taught for 30 years. In 2000 she became Distinguished Theologian in Residence at Vancouver School of Theology in British Columbia.

I never had the privilege of meeting Thomas Berry, but I have sat in lecture halls and online courses with people who knew him well. When the Parliament of World Religions came to Toronto, I agreed to work as a volunteer for an exhibit booth. This gave me access to the entire program and allowed me to sneak into a session led by Mary Evelyn Tucker. I already knew of her through a reading of Living Cosmology, Christian Responses to Journey of the Universe. It had been recommended by a friend in my local parish and it had already changed my perspective. Later I ran into Mary Evelyn again with her husband, John Grim, on a long series of elevators in the Convention Centre and after chatting, promised to write to her for advice. When I did so months later, she replied almost immediately, copying my note to several people in Toronto. This created a whole new world of university lectures, attendance at an online course presented through the Deep Time Network, meetings with a Toronto Passionist community and engaging with new friends, some of whom were Berry’s students. Thomas Berry’s teaching and influence has sent ripples far and wide.

Encountering Sallie McFague first was a good introduction to Thomas Berry, because the latter has a wider perspective, and his papers almost take it for granted that his readers have a good grounding in traditional Catholic Theology. But what has struck me subsequently is how well they both understood the coming climate crisis while most of us were ignorant. They also recognized the shortcomings of traditional Christian theology to cope with it and issued a warning.

Thomas Berry wrote poetry throughout his life, and I was delighted to encounter this poem:

Morningside Cathedral

We have heard in this Cathedral

Bach’s Passion

The Lamentations of Jeremiah

Ancient experiences of darkness over the earth

Light born anew

But now, darkness deeper than even God

Can reach with a quick healing power

What sound,

What song,

What cry appropriate

What cry can bring a healing

When a million year rainfall

Can hardly wash away the life destroying stain?

What sound?

Listen — earth sound

Listen — the wind through the hemlock

Listen — the owl’s soft hooting

in the winter night

Listen — the wolf — wolf song

Cry of distant meanings

woven into a seamless sound

Never before has the cry of the wolf expressed such meaning

On the winter mountainside

Morningside

This cry our revelation

As the sun sinks lower in the sky

Over our wounded world

The meaning of the moment

And the healing of the wound

Are there in a single cry

A throat open wide

For the wild sacred sound

Of some Great Spirit

A Gothic sound — come down from the beginning of time

If only humans could hear

Now see the wolf as guardian spirit

As saviour guide?

Our Jeremiah, telling us,

not about the destruction of

Jerusalem or its temple

Our Augustine, telling us,

not about the destruction of Rome and civilization

Our Bach,

telling us not about the Passion of Christ in ancient times,

But about the Passion of Earth in our times?

Wolf — our earth, our Christ, ourselves.

The arch of the Cathedral itself takes on the shape

Of the uplifted throat of the wolf

Lamenting out present destiny

Beseeching humankind

To bring back the sun

To let the flowers bloom in the meadows,

The rivers run through the hills

And let the Earth

And all its living creatures

Live their

Wild,

Fierce,

Serene

And Abundant life.

I entered the Episcopal Cathedral of St John the Divine in Manhattan every school day for three years in the early sixties, when I taught at a small private school in Morningside Heights. One of the cathedral’s many chapels served as the one for our school before the new school building had its own. Once I left a parcel in the chapel and found a back door open to go in and retrieve it – and feeling my way around the ambulatory on a dark later afternoon, realized the Cathedral’s immensity as the only person in that enormous space. Its subdean, who also served as as our school chaplain, was Edward West, who became Canon Tallis in the novels of my fellow teacher Madelaine L’Engle. The poem also is filled with the images of the Missa Gaia, composed by Paul Winter and others and premiered in the Cathedral in 1982. I sang in the premiere of that same work in Toronto about 25 year later bringing to this full circle.

Sally McFague would have liked this poem. In one her own books she writes about the power of metaphor and sees parables as falling into the category, saying:

“The shock, surprise or revelatory aspect – the insight into fatherly love – is carried in the parable of the Prodigal Son by the radicalness of the imagery and action. This parable, like many others, is economical, tense, riven with radical comparisons and disjunctions. The comparisons are extreme; what is contrasted however, is not this world versus another world, but the radicalness of love, faith and hope within this world.”

Both writers see the importance of stories and their symbolic value. Both have a poetic sensibility born of deep experiences in childhood. Thomas Berry speaks of a mystical experience as a small boy looking at a view from his North Carolina home and a sense of its importance.

“Beyond this site . . . was a meadow covered by white lilies rising above the thick grass. Whatever preserves and enhances the meadow in the natural cycles of its transformation is good; whatever opposes or negates it is not good”.

Sallie McFague speaks of a discovery at a very young age that one day she would no longer exist. She relates this in the introduction of spiritual autobiography in her book Life Abundant. At Vanderbilt University she taught a course in the biographies of others and had never documented her own until a student challenged her. She says that it came in several stages:

The first, which came in two stages, occurred when I was around seven years old. One day while walking home from school the thought came to me that someday I would not be here: I would not exist. Christmas would come and I would not be around to celebrate it.; even more shocking my birthday would occur, and I would not be present. It was not an experience of death- and the fear of it; rather, it was an experience of non- being: I simply would not exist. Eventually it began to turn into a sense of wonder that I was alive- and so were myriad other creatures.

The two were sensitive children who would become visionaries.

Both writers speak of the task of the coming twenty first century as ‘The Great Work’, a reckoning with what North American settlement and colonialism have done to despoil its lands. Both recognized the need to incorporating the cosmology now available through modern science within the Christian framework. To do so they both draw on the teaching of Teilhard de Chardin.

Sallie McFague in her book, The Body of God, builds on her earlier quest of broadening our understanding of God to explore a new understanding of nature. Along with Thomas Berry, she sees the necessity of looking at the creation stories emerging from science. She says:

“. . . To say God is creator is not to focus on what God did once upon a time, either at the beginning or during the evolutionary process, but on how we can perceive ourselves and everything else in the universe dependent on God now in terms of our cosmic story. . . Moreover, and of utmost importance, whatever may have been the mechanisms of evolutionary history in the past, evolution in the present and future on our planet will be inextricably involved with human powers and decisions”.

Thomas Berry also delved deeply into the writings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin who influenced him powerfully. The French Jesuit Priest, paleontologist, theologian and philosopher was responsible for the discovery of Peking Man and one of the earliest to view the evolutionary process from a spiritual perspective. In his essay, Teilhard in the Ecological Age, Thomas Berry observes:

“Indeed, he is the first person to outline in some full detail, and with some meaningful insight, the four phases of evolutionary process: galactic evolution, Earth evolution, life evolution, human evolution. He sees all this in its encompassing unity, and with such descriptive detail of the outer process and the inner forces that sustained the unfolding sequence. Probably no one at the humanistic, spiritual or moral level ever attended so powerfully to this evolutionary process as did Teilhard.”

Admiration of Teilhard was not a problem for McFague at Vanderbilt, or at an interdenominational school of theology in Vancouver. Drawing on Teilhard’s teaching could have been for Thomas Berry, had he not referred to himself as a “geologian” even after a loosening of adherence to dogma after Vatican II. Both Berry and Teilhard affirmed the beauty and value of the universe as the pre-eminent cosmology. They also shared a view that a materialistic view of evolution did not do it justice and saw a sacred dimension of its journey from its beginning.

A reassessment of theology demands a new look at creeds. The strength of creeds is that they deal with relationships. Problems arise when the connotations of images used in other eras may bring cultural associations that don’t sit well in our own. Both writers draw on their growing understanding of ecology in their reframing.

When considering God as patriarch, Sallie McFague notes that ‘Father’ can suggest both dominator and provider. The masculine predominance can also be problematic for women, as when one theologian quipped, “When God is male, the male is God”. It is important not to treat the Bible as the literal “Word of God” but delve into the stories and ponder what they say about relationships. Most of the stories emerge from a patriarchal tradition. Other images for God are possible as she notes:

“I have come to see patriarchal as well as imperialistic, triumphalistic metaphors for God in an increasingly grim light; this language is not only idolatrous and irrelevant - besides being oppressive to many who do not identify with it – but it may also work against the continuation of life on our planet.”

In her third book, Models of God, she offers new Trinitarian images: Mother, Lover and Friend. She wants these to be relational, both personally but also applicable in the wider context – “God so loved the World”. In expanding this new Trinity, she likens the first person to Mother as creator. All the associations of gestation, giving birth and lactation have real-world reference and suggest a different relationship with the world than a monarchical one. Mother also includes an element of tenderness towards the most vulnerable.

God as Lover – a new naming of the second person of the Trinity - is not meant to be sentimental, especially in an ecological context. “We have a tempter no other generation has had,” Sallie says, writing in a nuclear age, “We face the temptation to end life, to be the un-creators of life in inverted imitation of our creator”. Sin is not the failure to turn from the world and toward God, but a refusal of relationship toward all living beings in favour of the love of one’s self – to refuse to love all that God loves. In this model, God suffers along with humans and is present in our pain here and now. McFague says,

“What is needed on this view of salvation is not the forgiveness of sins so that the elect may achieve their reward, but a metanoia – a conversion or change of sensibility, a new orientation at the deepest level of our being- from one concerned with our own salvation apart from the world, but to one directed toward the well-being, the health of the whole body of the world”.

The third person, Friend, for Sallie is represented by the table fellowship of Jesus, where the Body of Christ is not an exclusive or elitist group but one that shares a meal. The Spirit is conceived as a friend to the world and acts in a way that fosters its well-being. Both God and humans are friends of the world. In the nuclear age it is an antidote to fear of the stranger. Boundaries of nations or species give way to the realization of sharing the planet. The outsiders are not our enemy but our sisters and brothers in an expanded world, where the best of human experience of companionship gives us this relational model of caring for all.

Thomas Berry drew upon world religions and cosmology to inform his deep understanding and practice of Christian religion and arrived at a different Trinitarian view The Trinity is, of course a complicated doctrine that tries to deal with paradoxes of transcendence and immanence, time and space, divine and human, mystery and revelation. “Never ask people what they believe,” observed one of my former parish priests. “Because you won’t like it”. We don’t have a language to deal with the Trinity. At its best it helps us with an understanding of divine and human relationships. But it also can avoid the rest of creation and our relationship to it.

Berry’s early life was thoroughly Catholic in its orientation. His growing interest in ecology led him to wonder why the church was not paying attention to what was clearly a moral and spiritual concern. “Christians are off in the distance as, indeed, are most of the professions and institutions of our society. . . Stewardship does not recognize that nature has a prior stewardship over us”, he said. The universe story must become prominent and inform religious sensitivities. He thought it was too late for a new religion and urged that all religions, especially his own, incorporate the new understandings: “The most needed of these insights is the realization that humans form a single community with all the other living things that exist on earth”. Moreover “We have established a discontinuity between the nonhuman and human components of the universe and have given all the rights to the human”.

The universe provides the basis of the Trinity in its basic tendencies – “differentiation, interiority and universal bonding” as Berry’s way to think about Father, Son and Holy Spirit which by contrast is a family model.

The universe story is one of immense creativity resulting in immense time and space with huge transformations – galaxies, formations of stars, creation of the elements, the supernova explosion, the creation of our own star, and the creation of the Earth as one of the planets, the creation of a living cell and the possibility of reproduction and photosynthesis, plants, animals and finally the human – every creation unique and individual in its differentiation. Our response to such differentiation is celebration

The incarnation can also be viewed in a new way. The writers of the New Testament never saw the Christ figure as an individual limited in time and space. In Colossians, Paul says “He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” The Gospel of John begins “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Such a universal sense, Berry says, is also present in other world religions that share this sense of interiority.

Universal bonding broadens our roles in faith communities to extend our reach not only to other humans but to all other species and forms of life of our common planetary home. We need to see our relationships through our experience of the natural world and our responsibility for it. This comes not chiefly through a focus on soul and inner life, but through a deep understanding of the universe story. The desire for a universe story resulted in the collaboration of Thomas Berry and Brian Swimme resulting in The Universe Story and later, the Journey of the Universe film, and even more recently the Noosphere Project videos hosted by Brian Swimme and produced by Human Energy.

Both Sallie McFague and Thomas Berry embrace the Gaia Theory as a way to envision the earth. McFague’s model of the universe is as God’s body. What is important is the notion of embodiment as an organic model, as opposed to the rational mechanical model of the planet described by science. We experience our own body. We first learn through our senses. We also use “body” to signify a community with whom we associate and take seriously. For those in the West, these bodies are Jewish and Christian, but we now know there are other cultural communities and faiths that created them. It allows all of us to use this common metaphor.

In his essay The Gaia Hypothesis: Its religious implications, Berry supports the idea of the Earth as organic. The hypothesis, developed by chemist James Lovelock and biologist Lynn Margulis and named after the Greek goddess of Earth, argues that Earth can regulate its systems of temperature and atmosphere, making it the only planet we know of that supports life.

Berry thinks that a cosmology of Earth is necessary from a religious perspective to replace the notion that Earth is a specific geographic location where we find ourselves – a street, a neighborhood or a country. The science of the last two centuries has given us an understanding of how miraculous Earth’s place in the universe really is. We respond to its landscapes and oceans; we are keen to travel and explore it. But our socialization via language has removed Earth’s nature as a living entity. Indigenous peoples understood this characterization, referring to the elements as brothers and sisters; they also developed liturgies to mark their changes relating in their own life passages. Natural elements were subjects and could be addressed by an intimate “thou”.

Both insist that humans regard all other species on the planet as subjects, not objects.

McFague distinguishes two ways of viewing the world, citing much nature writing as opening to “surprise and delight”, often by close observation of a small subject – like a single wildflower or a goldfish. She contrasts this interpretation with the astronauts’ view of earth from space, framing it as an object, however beautiful it was. The difference, she says, is the contrast between the arrogant eye and the loving eye. Any seeing comes from the perspective of the viewer. The arrogant eye looks for the usefulness to the self – what’s in it for me. McFague also characterizes this as the patriarchal eye, a common one in the culture of the west. She notes, “We never ask of another human being, ‘What are your good for?’ but we often ask that question of other life forms and entities in nature. The assumed answer is, in one form or another, ‘good for me and other human beings”.

Thomas Berry agrees with the need for a reorientation toward intimate experience of our surrounding world – the stars, the skies, the oceans, the trees – all those parts of nature that engage the senses of sight, sound, taste, smell and touch and awake wonder and awe. He stresses, as Sallie McFague does, the necessity of reengaging with the entire earth community.

“We need to move from a spirituality of alienation from the natural world to a spirituality of intimacy with the natural world, from a spirituality of the divine as revealed in the written scriptures to a spirituality of the divine as revealed in the visible world about us, from a spirituality concerned with justice only for humans to a spirituality of justice for the devastated Earth community, from the spirituality of the prophet to the spirituality of the shaman. The sacred community must now be considered the integral community of the entire universe and more immediately, the integral community of the planet Earth.”

Such attitudes require agency, Sallie McFague says that in looking at the contemporary world, one must start economics and she outlines a traditional economic model. A simple definition of economics is the management of scarce resources. It assumes that individuals are primarily motivated by self-interest. rely on it and all ultimately benefit. The world is viewed as an object – a machine with many parts. The goal of the economy is growth and what is measured is gross domestic product. The role of the human is to be a consumer; the emphasis is on freedom of an individual who is sinful – flawed but free to pursue the role of individual happiness. The problem with the model as a worldview is that not all enjoy the good life. One billion may currently have it, but another six and a half billion don’t – and want it. The planet has limited resources and the wealthiest control and use most of them.

An ecological worldview is different. The scarcity of resources remains a given. The model is the household – the oikos – and the good of all members in the long term. Fulfilling human need rather than human greed is the objective. The world is a subject - a body, an organism, full of related diverse life forms. The goal is sustainability with a focus on restorative justice, and the human is a care giver. The emphasis is on creation – on incarnation, resulting in a response of gratitude. The goal is recognition of one’s proper place including recognition of privilege for those who have it – and moving to create a more equitable place for those who do not. The problems relate to the discrepancies in a global world. However aspirational the goals are, they require adherence to house rules: take no more than your share, clean up after yourself, keep the house (the planet) in good order. We have work to do that involves much rethinking and practice.

What would action look like for Thomas Berry?? In An Ecologically Sensitive Spirituality, he outlines it. He begins with the damage caused by the Doctrine of Discovery and its consequences. Indigenous peoples welcomed explorers without any knowledge of what would follow. What would have happened if the visitors had responded with wonder to the beauty of the new lands they encountered, so different than those of the lands they departed from. Instead:

“Unfortunately. these people from across the sea thought they already knew everything. They brought with them a book, the Bible, as their primary reference as regards reality and value. Though a work of great spiritual significance, this Bible has also been used to justify the domination of peoples and land in various parts of the world. Moreover, the book has contributed to the inability of humans to see the natural world as revelatory. Revelation was in scripture alone, not in nature itself.”

The natural world the settlers invaded had much to teach them. What also caused alienation was the domination of the mind in the humanist formation of the west. Added to both were the scientific emphases of Newton and Descartes that saw nature in quantitative rather than qualitative terms. Nature contained objects to be exploited for human advantage. Berry notes:

“While Earth’s resources are finite, what is not limited is our desire to understand, to appreciate and to celebrate the Earth. We do need endless progress, but not, however in material development. Only an increase in aesthetic appreciation and spiritual experience can be without limit.”

What is needed, he says, is a reorientation toward intimate experience of our surrounding world – the stars, the skies, the oceans, the trees – all those parts of nature that engage the senses of sight, sound, taste, smell and touch and awake wonder and awe. Thomas stresses, as Sallie McFague does, the necessity of reengaging with the entire earth community.

“We need to move from a spirituality of alienation from the natural world to a spirituality of intimacy with the natural world, from a spirituality of the divine as revealed in the written scriptures to a spirituality of the divine as revealed in the visible world about us, from a spirituality concerned with justice only for humans to a spirituality of justice for the devastated Earth community, from the spirituality of the prophet to the spirituality of the shaman. The sacred community must now be considered the integral community of the entire universe and more immediately, the integral community of the planet Earth.”

We need air, food, water and shelter for survival. We share these needs with other species. The journey of the universe has also given humans the gift of consciousness which leads to sensitivity and responsibility, not just for ourselves, but for all living species and our common home. Science has given us a wealth of new learning. We can no longer rest solely in the interior life when we have been given consciousness of the physical order. There is a new role for each of us – the integral ecologist who understands the sacred nature of the universe journey. Such a person plays an essential role in many fields where the ecological implications are understood – law, medicine, education, religion and politics. Thomas concludes the paper saying,

“Only the universe is a text without a natural context. Every particular being has the universe for context. To challenge this basic principle by trying to establish the human as self-referent and other beings as human referent in their primary value subverts the most basic principle of the universe. Once we accept that we exist as integral members of this larger earth community of existence, we can begin to act in a more appropriate human way. We might even enter once again into that great celebration, the universe itself.”

As well as a new orientation of economics, both writers call for new liturgies in faith communities and new reorientations of education, politics and law. That is the Great Work for us now. Theologian Matthew Fox notes that as Berry defined ecology as “functional cosmology”, indeed we can also draw on Thomas Aquinas, whose name Thomas Berry chose as his own with wisdom. Aquinas saw joy, love and beauty as the key attributes of the universe. In moving toward action, we must draw upon the “exuberance of existence” where nature wants to reveal itself to us through creation – and join in the joy of creation.

When we are arrogant

Any faith that thinks it has the total answer and must impose it on others is dangerous when it uses domination. For the record, here is a thanksgiving offering from First Nations People that North American Christians thought were heathen, called them savages and tried to destroy their thousands of years of faith. In a time of climate crisis. this teaching is precisely what we now need to recover and learn:

Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address

This Thanksgiving address was used by the six nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) to open and close major gatherings or meetings. The prayer was also sometimes used individually at the beginning or end of the day..

The People

Today we have gathered and we see that the cycles of life continue. We have been given the duty to live in balance and harmony with each other and all living things. So now, we bring our minds together as one as we give greetings and thanks to each other as people.

Now our minds are one.

The Earth Mother

We are all thankful to our Mother, the Earth, for she gives us all that we need for life. She supports our feet as we walk about upon her. It gives us joy that she continues to care for us as she has from the beginning of time. To our mother, we send greetings and thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Waters

We give thanks to all the waters of the world for quenching our thirst and providing us with strength. Water is life. We know its power in many forms- waterfalls and rain, mists and streams, rivers and oceans. With one mind, we send greetings and thanks to the spirit of Water.

Now our minds are one.

The Fish

We turn our minds to the all the Fish life in the water. They were instructed to cleanse and purify the water. They also give themselves to us as food. We are grateful that we can still find pure water. So, we turn now to the Fish and send our greetings and thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Plants

Now we turn toward the vast fields of Plant life. As far as the eye can see, the Plants grow, working many wonders. They sustain many life forms. With our minds gathered together, we give thanks and look forward to seeing Plant life for many generations to come.

Now our minds are one.

The Food Plants

With one mind, we turn to honor and thank all the Food Plants we harvest from the garden. Since the beginning of time, the grains, vegetables, beans and berries have helped the people survive. Many other living things draw strength from them too. We gather all the Plant Foods together as one and send them a greeting of thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Medicine Herbs

Now we turn to all the Medicine herbs of the world. From the beginning they were instructed to take away sickness. They are always waiting and ready to heal us. We are happy there are still among us those special few who remember how to use these plants for healing. With one mind, we send greetings and thanks to the Medicines and to the keepers of the Medicines.

Now our minds are one.

The Animals

We gather our minds together to send greetings and thanks to all the Animal life in the world. They have many things to teach us as people. We are honored by them when they give up their lives so we may use their bodies as food for our people. We see them near our homes and in the deep forests. We are glad they are still here and we hope that it will always be so.

Now our minds are one.

The Trees

We now turn our thoughts to the Trees. The Earth has many families of Trees who have their own instructions and uses. Some provide us with shelter and shade, others with fruit, beauty and other useful things. Many people of the world use a Tree as a symbol of peace and strength. With one mind, we greet and thank the Tree life.

Now our minds are one.

The Birds

We put our minds together as one and thank all the Birds who move and fly about over our heads. The Creator gave them beautiful songs. Each day they remind us to enjoy and appreciate life. The Eagle was chosen to be their leader. To all the Birds-from the smallest to the largest-we send our joyful greetings and thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Four Winds

We are all thankful to the powers we know as the Four Winds. We hear their voices in the moving air as they refresh us and purify the air we breathe. They help us to bring the change of seasons. From the four directions they come, bringing us messages and giving us strength. With one mind, we send our greetings and thanks to the Four Winds.

Now our minds are one.

Closing Words

We have now arrived at the place where we end our words. Of all the things we have named, it was not our intention to leave anything out. If something was forgotten, we leave it to each individual to send such greetings and thanks in their own way.

Now our minds are one.

Thanksgiving Address: Greetings to the Natural World English version: John Stokes and Kanawahienton (David Benedict, Turtle Clan/Mohawk) Mohawk version: Rokwaho (Dan Thompson, Wolf Clan/Mohawk) Original inspiration: Tekaronianekon (Jake Swamp, Wolf Clan/Mohawk).

Available through the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.