My writings - and those of others.

Re-Wilding

Those of us who live near ravines in Toronto are blessed with an escape into a natural world on the edge of office and residential towers. As part of the recent University of Toronto’s alumni weekend, a lecture advertised as “Stress -Free” and entitled Re-Wilding Toronto, The Billion Dollar Dream - was an obvious choice.

The public lecture was filled with a wealth of information and excellent slides - some of which I couldn’y resist snapping and sharing here. Eric Davis is currently a PhD candidate, but he brings a wealth of work experience and a passion for restoration.

We learned that the Toronto Ravines are one of the world’s largest ecosystems, that cover 27,000 acres or one fifth of the city.

What an uninformed public does not know is that after years of neglect the ravine system is on the verge of collapse:

Eric Davis is a gifted instructor and used good analogies throughout. His points are illustrated in the mini-slide show below.

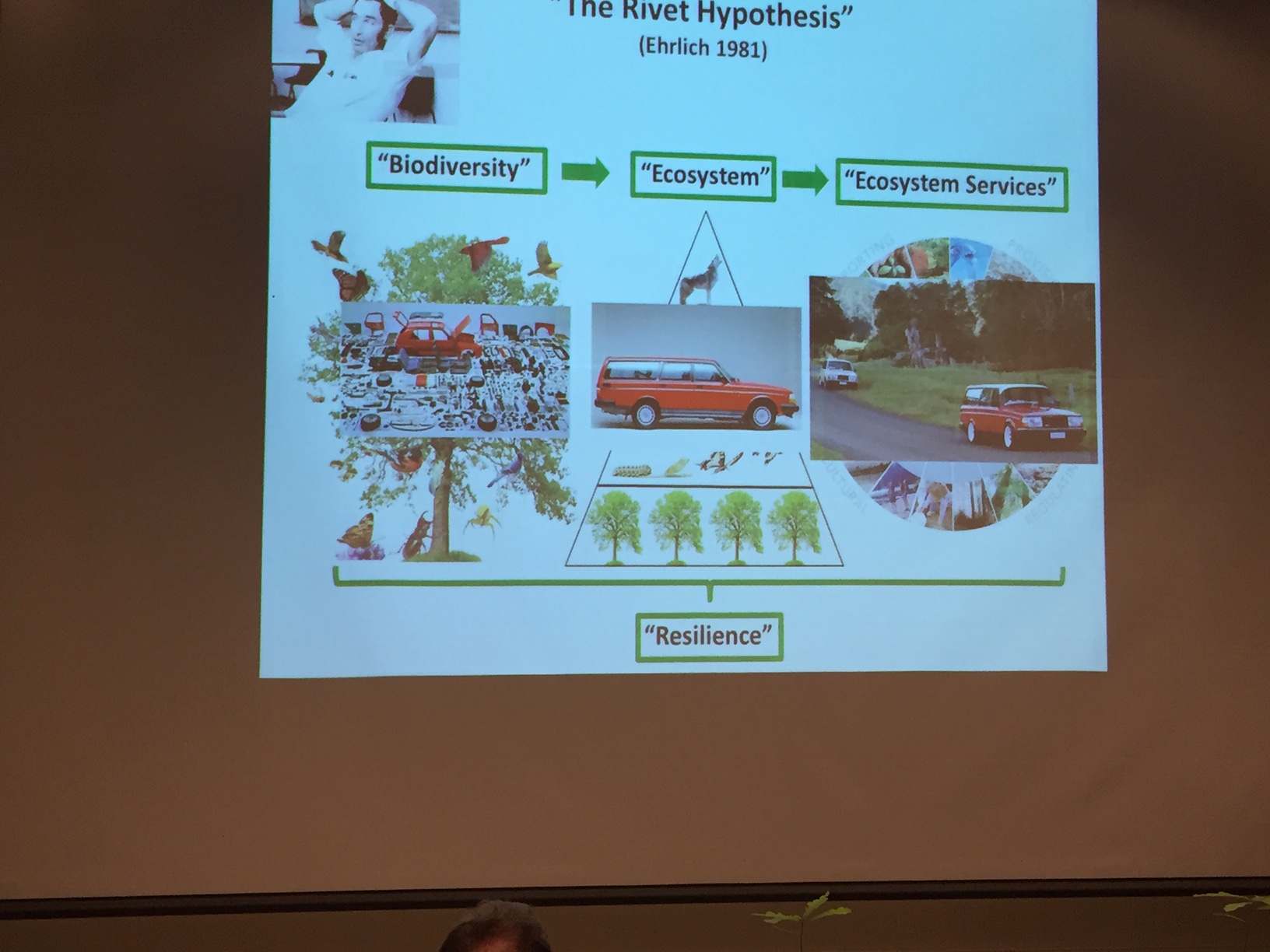

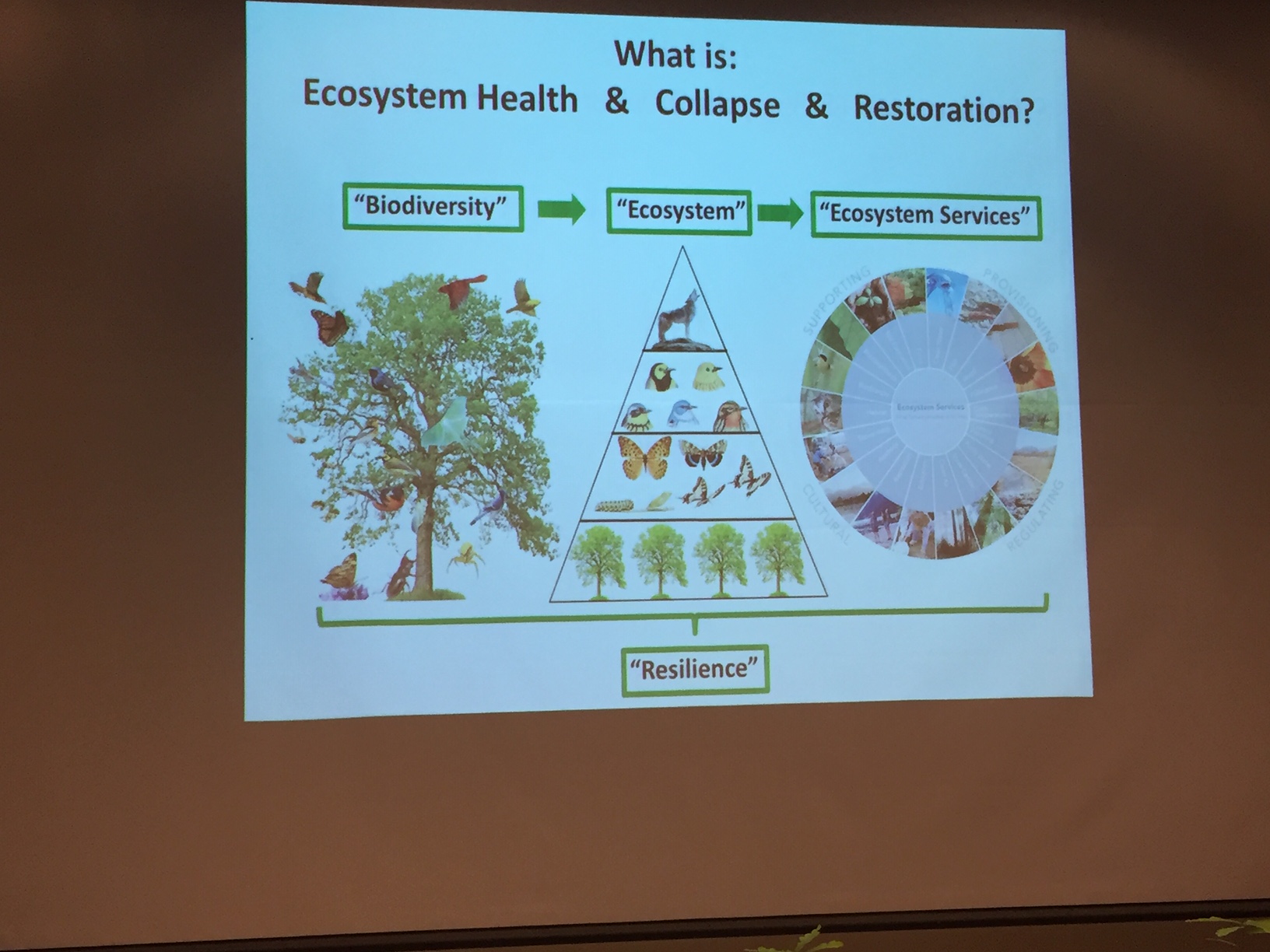

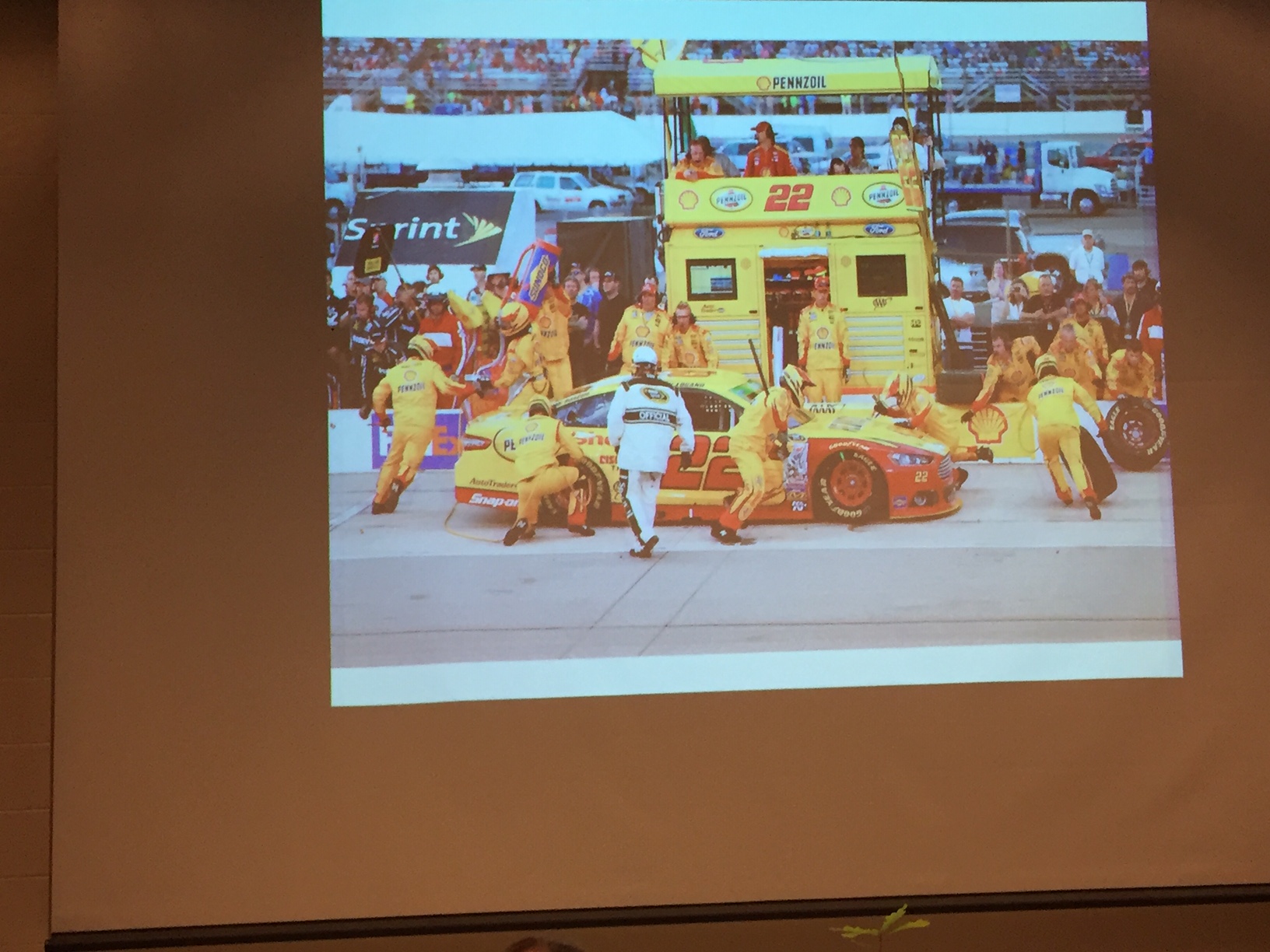

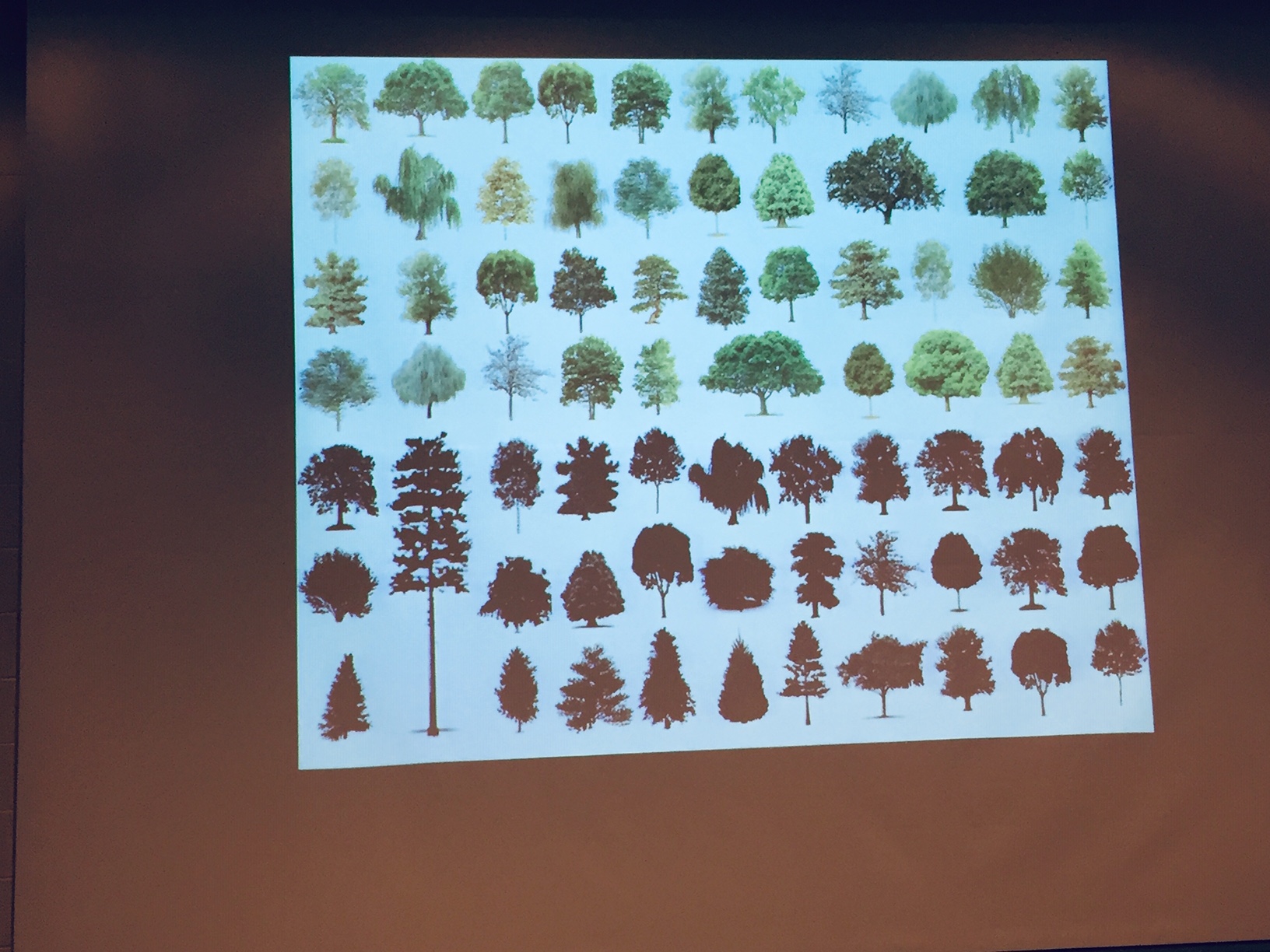

He started by showing us that trees are part of a system of biodiversity on which an entire ecosystem depends to produce a number of services on which other forms of life - including ourselves - depend. The intricacy of the system can be compared to a racing car - in which the importance of the most minute parts will determine the success of the race - a comparison that another forester named the rivet hypothesis. When the Nascar race happens, the integrity of the parts is crucial and the emergency repair team is on it with repairs in seconds. We need a comparable repair pattern for the trees in our ravines.

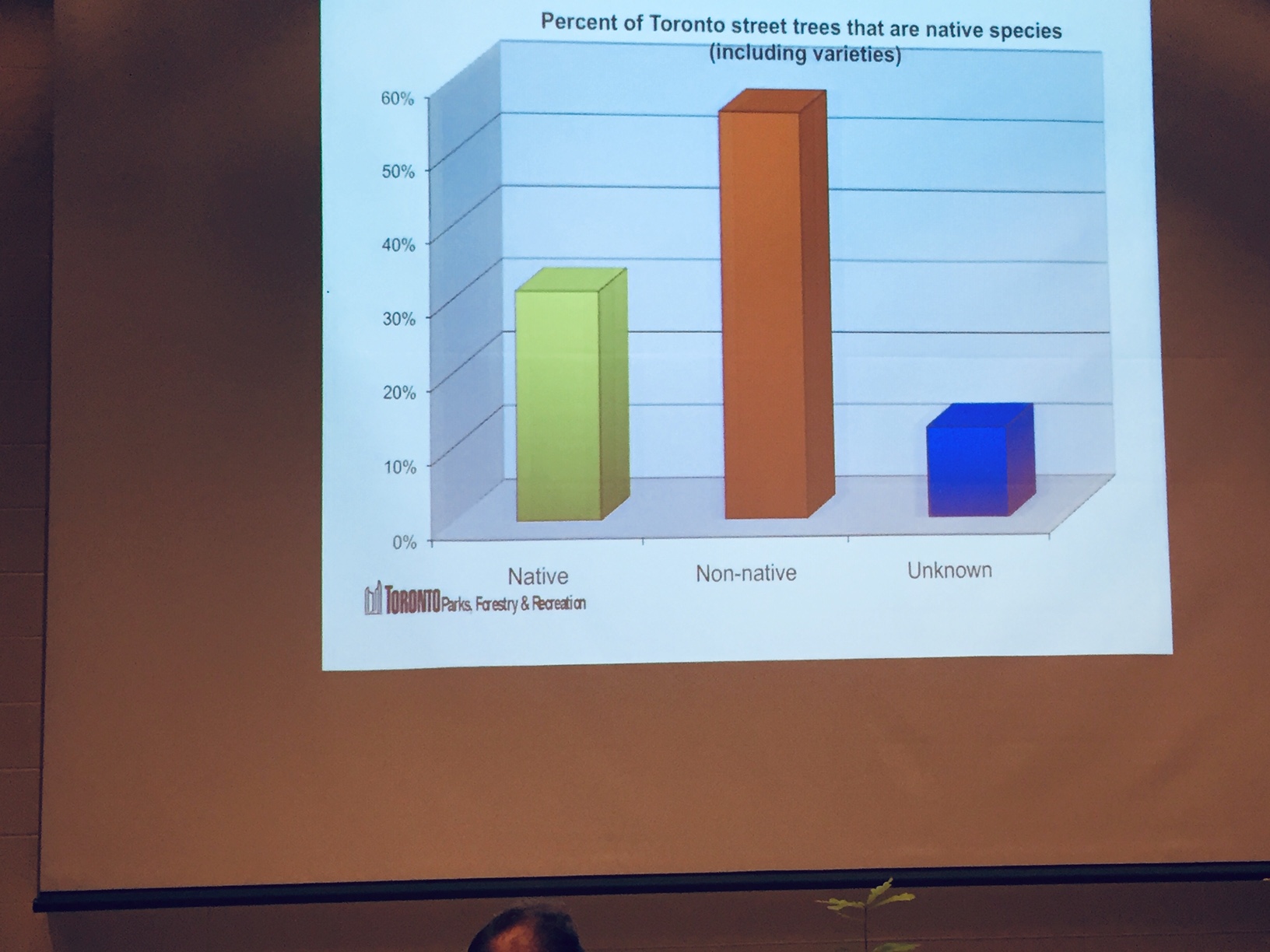

What has happened is the ravines have become invaded by non native trees- brought in by the owners of adjacent properties over the past decades - and the percentages of these are growing.

A study of the Rosedale Ravine 40 years ago has provided a baseline to study the changes:

The time lapse shows the urgency of the need for change. But unlike too many of the studies that we read about, Eric Davies has some clear solutions. The summary of the study can be read here and includes the following:

A Tree inventory has been completed

Other inventories are not under way - both native and non-native vegetation, mammals, birds and insects

Citizens are becoming involved in local studies and inventories

Schools and households are encouraged to collect, plant and grow local plants and trees to prepare for reforestation.

Perhaps the most important answer came from a response when a questioner wondered why we aren’t planting for a future client change. The answer - trees have been adapting to changing conditions for thoustands of years. We can probably trust them to do so - and do what we can to help them flourish.

And the billion dollar price page? A cathedral generated two billion in one day for restoration. Perhaps it is time to get our priorities right when we compare the importance of an ecosystem to our future.

Plan B isn't Planet B

No Planet B is the title of a current post from the Parliament of World Religions. They are aunching a webinar series entitled Faith and Climate Webinar series and you can find out more about that here.

Their Climate Action Program is also launching a special "WebForum" page on the Parliament's website to provide background about the Faith and Climate Webinar Series and begin a discussion of webinar topics ahead of time. The WebForum will feature a lead essay by a panelist from the upcoming Faith and Climate webinar, with written responses from other panelists and invited experts from the field, as well as comments and questions from readers. Each WebForum topic will include background information about the specific webinar topic, with links to further reading in anticipation of the webinar itself.

Plastics - A mini-history

To take on plastics is to take on consumerism itself:

For some time we have agreed that too much is bad – but without doing anything about it. Scientists, though were aware of it much earlier. The current focus on microplastics – tiny bits entering the food chain – has increased awareness. As well as the perceptions changed by images of waste islands at sea or suffering animals, there has been a shift from seeing plastics and other waste as litter to understanding of it as a dangerous pollutant.

Climate change is hard to understand – but plastics are everywhere in front of our nose. I believe I share basic ignorance with most around me. What is plastic, who makes it and where does it come from? I turned to an article by Stephen Buranyi in the Guardian published last November for some basic information. It’s comprehensive, thorough and quite long so I am summarizing with some direct quotations:

·Plastic is a global industrial product.

·Plastic is a catch-all term for the product made by turning a carbon-rich chemical mixture into a solid structure.

The raw materials come from fossil fuels, and many of the same vast companies that produce oil and gas also produce plastic, often in the same facilities.

The story of plastic is the story of the fossil fuel industry – and the oil-fueled boom in consumer culture that followed the second world war.

To make it requires coal, water and air

By developing new plastic products – like Dow’s invention of Styrofoam in the 1940s, or the multiple patents held by Mobil for plastic films used in packaging – these companies were effectively creating new markets for their oil and gas

Thin plastic wrapping was introduced in the early 1950s, displacing the paper and cloth protecting consumer goods and dry cleaning. By the end of the decade, DuPont reported more than a billion plastic sheets sold to retailers.

At the same time, plastic entered millions of homes in the form of latex paint and polystyrene insulation.

Soon, plastic was everywhere, even in outer space. In 1969, the flag that Neil Armstrong planted on the moon was made of nylon.

The following year, Coke and Pepsi began replacing their glass bottles with plastic versions.

Plastic did more than merely take the place of existing materials, leaving the world otherwise unchanged. It actually helped kickstart the global economy’s shift to disposal consumerism.

Plastic meant profit – but it also meant rubbish. A backlash started in 1969 heavily opposed by the industries that produced it.

Rather than blaming the companies that had promoted disposable packaging and made millions along the way, these same companies argued that irresponsible individuals were the real problem.

Household recycling was later seen as the answer – a solution pushed by the manufacturing industries as simple and effective. The problem with these rosy predictions was that plastic is one of the worst materials for recycling.

In the intervening years, global plastic production has rocketed from some 160 million tonnes in 1995 to 340 million tonnes today. Recycling rates are still dismally low.

Plastic isn’t just an isolated problem that we can banish from our lives, but simply the most visible product of our past half-century of rampant consumption.

What prompted me to do more research on this was after reading the article on bioplastics (materials based on plants rather than fossil fuels) in Paul Hawken’s Drawdown, a book that I highly recommend in my book section here on the site. You can also go to the related Website.

I like the idea of a Drawdown challenge after just completing one. I want to be sure that a future one related to plastics makes me learn more about the industrial side and question its impact - not just my personal use.

The Ont. Endangered Species Act

I’ve been very favorably impressed by the newly named Broadview, a publication that was formerly known as the United Church Observer. The national monthly print publication is now available in newsletter format and subscribers can read excellent articles on a number of issues that concern us all. A recent article deals with proposed changes in the Ontario Endangered Species Act and you can read it here.

Most of us are much too absorbed by our personal concerns to pay attention to the fact that we are living in one of the most massive animal extinctions that have taken place for millions of years. A few concerned individuals and groups do care and monitor public policy. Proposed changes by the Ontario government are problematic. Your local MPP should know of your concern when you voice it.

On Earth Day

I’m almost embarrassed to admit that this is the first Earth Day that I have taken seriously – but at least there has been some good preparation. It includes encountering the writings of Thomas Berry and his students and followers last August and becoming immersed in the works ever since. It includes attending the 2018 Parliament of World Religions and meeting the diversity of faith-based groups head on. It includes attending book launches, student research presentations and a day long Symposium on reducing our carbon fossil fuel dependency. It includes encountering the Deep Time Network and joining it. Finally it includes reading two recent books – Tony Clarke’s Getting to Zero, Canada Confronts Global Warming and Paul Hawken’s Drawdown – the latter that encouraged me to join the Toronto team this past month.

Clarke knew about the change of government in Ontario but the recent election in Alberta would be concerning when it is so opposes his case for reframing a Canadian economy hugely dependent on extracting bitumen from tar sands with its subsequent effects on economy and ecology. He faults the national government for its oxymoronic aims to protect the planet and grow the economy. He does provide a clear strategy to wean ourselves from our fossil fuel addiction, but cautions how much that depends on a bottom-up advocacy from a consortium of citizens’ groups. I admire his emphasis on dealing with the human side of the economy to drive the process.

I am convinced nevertheless that the greatest challenge faces traditional religions because what is required is a drastic re-framing of their cosmologies to include what we now know from science. Western Christianity has played a key role in both encouraging the growth of science and technology but also by ignoring it. As Thomas Berry says:

The solution then is not a case of restoring a religious, spiritual, moral or humanist tradition. It is a case of reordering the human in its entire relationship with the planet on which we live, a mission for which Christians are not especially suited, since we have seldom shown any extensive regard for the creation process, dedicated as we have been since the thirteenth century to a primarily redemptive task. (The Christian Future and the Fate of Earth)

There are a growing number of people who accept global warming and its implications for climate change and the active advocacy of the young is a sign of hope. There are a much smaller number that recognize the need for a new role for religions. Theirs is a crucial role – and they must encounter one another with humility and work together to create that role.